Destigmatizing mental health

How therapists think we should destigmatize mental health

I never needed to be convinced that destigmatizing mental health mattered.

I was born to a progressive, Irish-American family in the San Francisco Bay Area; where ideals of acceptance ran as thick as the fog. I was exposed to schizophrenia by way of pacing, muttering Cousin Ellen at that Thanksgiving when she got to leave the hospital. I learned about invisible illnesses, too, witnessing my grandmother in her depressive episodes.

It has been easy for me to believe in mental health. But, belief alone has not been enough to destigmatize mental health.

Most US citizens hold stigmas around mental illness. And, over the last 70 years, more of us have taken on the belief that people with mental illness are dangerous.

To destigmatize mental health, we well-intentioned folks will need to get up and actively enact change. Here’s how evidence-based research and expert clinicians suggest we do that.

The importance of mental health awareness

Awareness is a foundational tool for destigmatizing mental health. In the past century, huge gains have been made through concerted, large-scale efforts to bring attention to the matter.

Mental Health Awareness Month — observed in May each year — started in 1949 after four decades of tireless advocacy by Mental Health America.

In 1992, the World Health Foundation established October 10th as World Mental Health Day with the momentum garnered by organizers at the World Federation for Mental Health.

Thanks to these efforts, millions of people have improved their literacy in mental health care. But, information alone isn’t enough to combat the powerful force of stigma.

Impact of stigma on mental health

A stigma is a complex social phenomenon where stereotypes and biases result in barriers that inhibit access to essential resources.

Dr. Patrick Corrigan and Dr. Amy C. Watson — two leading experts on stigma in mental health care — found that these stigmas could be understood through two lenses:

- Self-stigma: “the prejudice which people with mental illness turn against themselves”

- Public stigma: “the reaction that the general population has to people with mental illness”

The popular conversation around destigmatizing mental health often focuses on self-stigma, and aims to solve the problem of people who do not seek care due to their own held beliefs.

However, a total view of the issue will require material challenges to the public stigma that results in reduced opportunities for work, housing, and health care.

Strategies to reduce mental health stigma

I’ve always prided myself on “supporting” mental health. But what does that even mean?! If I have not taken any steps to actively dismantle the stigmas around mental health issues, have I actually “supported” the cause?

The uncomfortable and honest answer is no. I can find comfort, however, by turning to a robust body of evidence-based research.

A global community of experts found three proven strategies to destigmatize mental health:

- Education

- Contact

- Activism

Education and awareness

Education and awareness are important weapons against stigma that elevate mental health issues to a community-level concern.

Literacy programs like Mental Health First Aid do this by offering training to identify, address, and prevent mental health challenges. In fact, the program has trained more than 2.5 million people on key intervention tactics, and with measurable results.

In an early study, Mental Health First Aid was found to create “significant improvements in knowledge about treatments, improved helping behaviors, greater confidence in providing help to others, and decreased social distance (which is one indicator of stigma)” (Stuart).

Encouraging open conversations

While education and awareness are helpful antidotes to stigma, they tend to speak to mental health care in somewhat abstract, generalized terms. To destigmatize mental health care, we need to deeply engage at a personal level.

After education, social contact has been found to be an essential part of destigmatizing mental health care. Members of the general population can proactively seek interpersonal exchanges with those who have lived experiences of mental illness. By increasing exposure to the realities of mental health issues, we can disconfirm stigmatizing beliefs.

One of the best ways to do this is to share your own experiences of mental health, as much as it feels safe to do so. If you’re in a position of (relative) social privilege, use it to model disclosure! By sharing your own experiences, you can give others the psychological safety to offer their own stories.

Advocating for mental health parity in healthcare

Action speaks louder than words. This is especially true of enacting social change.

Protest has been found to be the third part of the fight against stigma, with a particular focus on the general public activism to address:

- Low investment in behavioral health within the broader health care system

- Inequitable access to mental health care

- Public policies that restrict access to care

There are a number of organizations inviting volunteers to get involved in mental health advocacy. Among them is the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). There's also StigmaWatch: an Australian-based group holding mass media accountable for stereotypes about mental illness. One study found their work reduced negative portrayals of depression from 33% (in 2008) to 10% (2010), to 5% in recent years.

The role of mental health professionals

Therapists, counselors, and other providers sit at the crux of destigmatizing mental health. Beyond delivering mental health care, these professionals carry unmatched experience with the pervasive problems preventing individuals from getting the care they need. And, everyone can borrow from their institutional knowledge for inspiration in the fight against stigma.

Destigmatizing mental health treatment

One of the most significant steps a person can take to address their own mental health is to find a provider or similar care like a support group. We all can make that step easier by avoiding language that stigmatizes treatment.

Most of us have learned a lot of incorrect and stigmatizing ideas about therapy that have creeped into our everyday language, from calling psychologists “quacks,” to using “you need help” as a heat-of-the-moment insult. Unlearning this language is a critical piece of the work to destigmatize mental health disorders.

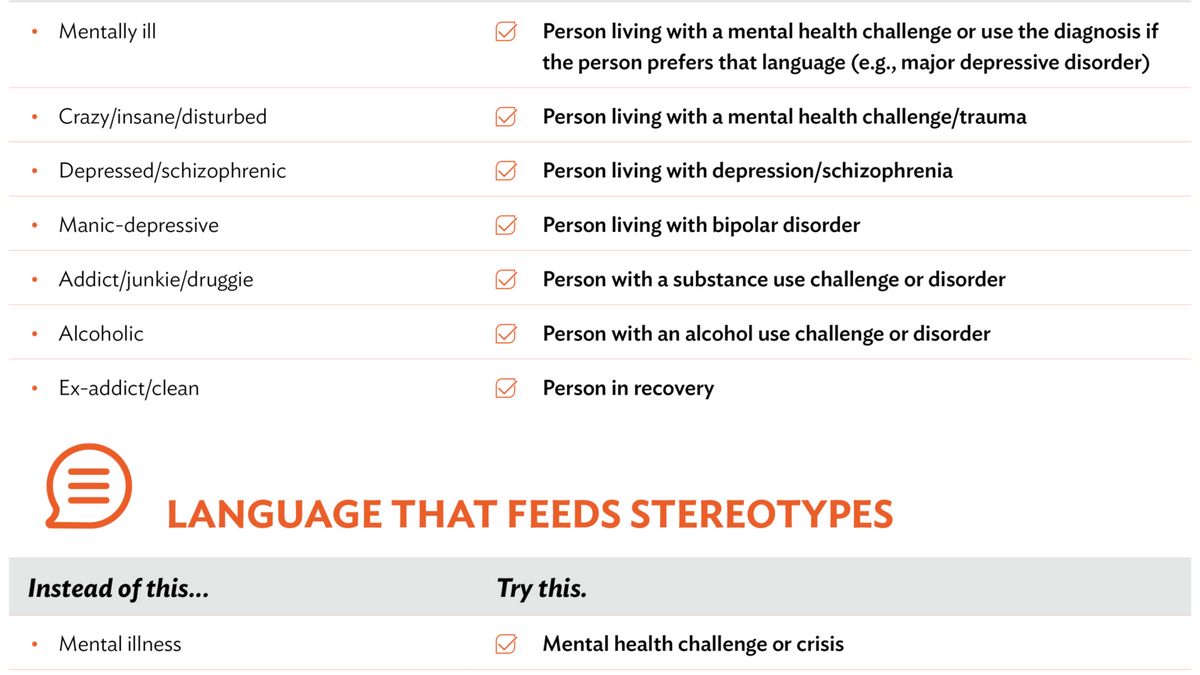

Person-first language and trauma-informed care

Everyday folks like myself aren’t qualified to diagnose, psychologize, or deliver therapeutic interventions to mental illness. That work belongs singularly with trained and licensed clinicians.

However, we can adopt some clinical approaches to language to avoid stigmatizing mental illness.

An important principle of trauma-informed care is Safety. By striving to choose words that do not enact further harm, we can promote both physical and psychological safety. A related principle is that of Humility and Responsiveness; where biases and inequities are acknowledged and addressed directly.

People-first language is a helpful — but not universal — framework for applying principles of trauma-informed care, putting “the focus on the individual, not their disorder or diagnosis.”

Person-first language is a valuable model for studying how our words can subvert or support stigma. However, it isn’t always appropriate to use it. Some may appreciate how person-first language (example: person with bipolar disorder, people who are blind) separates them from their condition. Others may identify inseparably with their condition, preferring identity-first language (example: bipolar person, blind people).

Our advice? Take your cues from the person you’re talking about, using a well-educated toolkit that includes person-first language.

Participating in community and anti-stigma initiatives

I’m grateful that my early experiences had exposed me to the importance of mental health. But, I need to do more.

It isn’t reasonable to think that awareness alone will be sufficient in the struggle against stigma. Nor is it reasonable to think that professionals can solve this problem alone.

In order to destigmatize mental health, we all need to get involved in anti-stigma initiatives. We need to protest unjust policies, put pressure on influential systems, and organize action to address stigma head-on.

How to destigmatize mental health

We all have the power to destigmatize mental health problems by working to advance education, exposure, and activism. It’s true that we need to expand awareness of mental health. And, it’s even more true that concerted action is the only way to enact change.

The importance of collective action

Stigmas around mental health challenges have been socialized over centuries and generations. Barriers to care have been deeply embedded into the United States healthcare system in a myriad of ways. And, the folks at the fore remain persistently under-valued, under-resourced, and under-paid.

The pervasiveness of the problem lends itself to fear and hopelessness. But, as with any great cause, destigmatizing mental health can be achieved if we take action together.

We can lean on the knowledge of researchers and clinicians to self-educate. We can engage in open conversations to get into deeper contact with experiences of mental disorders. And, we can volunteer and donate with any of the hundreds of organizations taking action against stigma.

Creating a more inclusive society for people with mental health conditions

By actively working to destigmatize mental health problems, we can make a meaningful impact on the lives of our family members, friends, and communities.

Even better; we can reimagine our understanding of mental health to better value neurodiversity.

Can you envision a world where mental health conditions aren’t classified as either “healthy” or “an illness”? Perhaps, then, we could adopt an attitude that all mental health experiences are worthy of care.

The good news is that such a world is possible. But, it will require action.

May 2, 2023

Looking for a therapist?

Get tips on finding a therapist who gets you.

By submitting this form, you are agreeing to Alma's privacy policy.