How Therapists (Really) Measure Progress

What is the difference between good therapy, and great therapy?

Most therapists have dedicated their life’s work to improving the mental health of their clients. They know, more than anybody, what high-quality mental health care looks like.

But, there is no consensus within health care systems on the best way to measure quality. This is a huge problem at a time when behavioral health faces unprecedented demand, a shortage of providers, and systemic barriers to access.

Alma surveyed over 200 therapists to understand how therapists measure progress. The result? We found clear opportunities for tech platforms, insurance companies, and mental health care providers to establish a universal definition of quality.

The role of assessments in therapy

A clinical assessment is a survey or interview that aims to capture the current state of a client’s behavioral health. And, while the idea of an assessment is easy enough to understand, it’s a fairly complex concept in practice.

Clinicians hold a healthy amount of skepticism for how these assessments are used by insurance providers, researchers, and technology platforms. As a result, there isn’t a universal approach to measuring outcomes or quality of care.

By surveying hundreds of therapists, Alma set out to learn exactly how therapists are — and aren’t — measuring the progress of their clients.

How therapists use assessments

Some common clinical assessments used by therapists are:

- PHQ-9: A questionnaire to help screen for and evaluate depression

- GAD-7: A questionnaire to help screen for and evaluate generalized anxiety disorder

- AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test): A method of screening for unhealthy alcohol use

- ORS (Outcome Rating Scale): A measure designed to assess areas of life functioning known to change as a result of therapeutic intervention

These assessments have many uses, like assisting in diagnosis of mental health conditions and monitoring progress in treatment for these conditions.

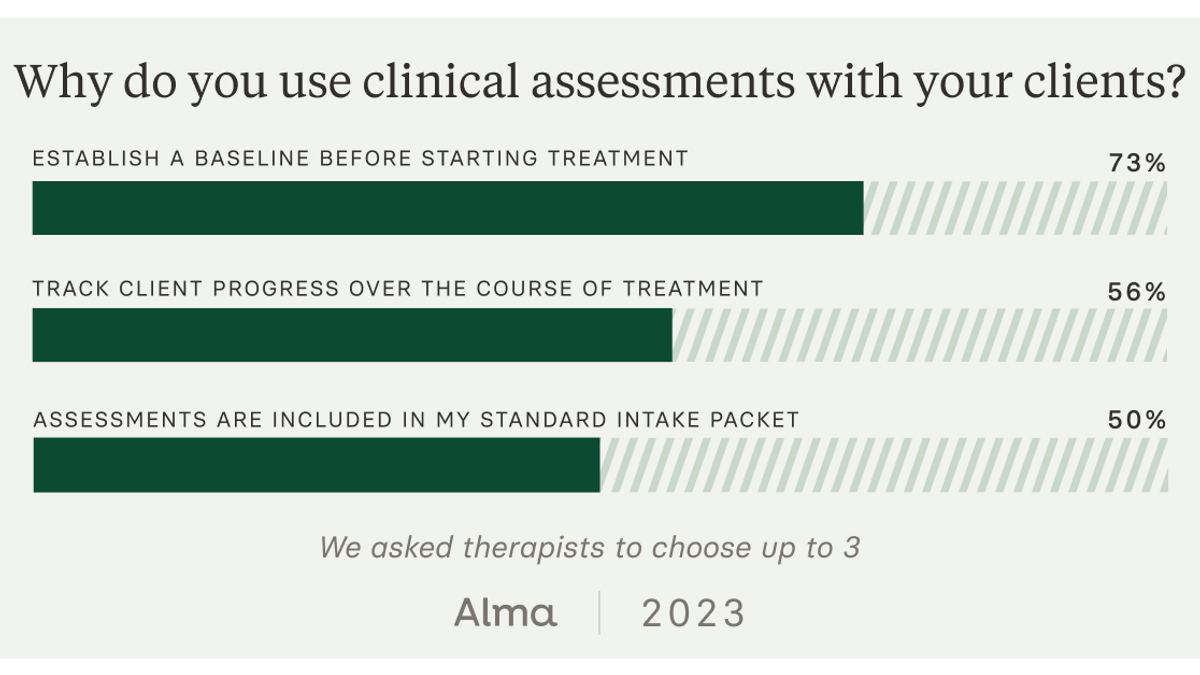

Alma’s survey found that 87% of therapists are routinely using clinical assessments, and 70% of those therapists find them useful for establishing a baseline for new clients. This snapshot can set up a helpful before-and-after for clinicians and clients to track what’s working.

Many therapists, however, feel these assessments offer an incomplete view of improvement during care. In fact, 30% of therapists surveyed did not find assessments to be useful in tracking clients’ progress over time.

So, why are therapists less likely to continue to use assessments as a part of ongoing care, despite believing in their value?

While therapists do value using clinical assessments for a “before and after” view, they are less confident in the utility of that data during care. And, they have serious concerns about how that data is used.

How insurance companies use assessments

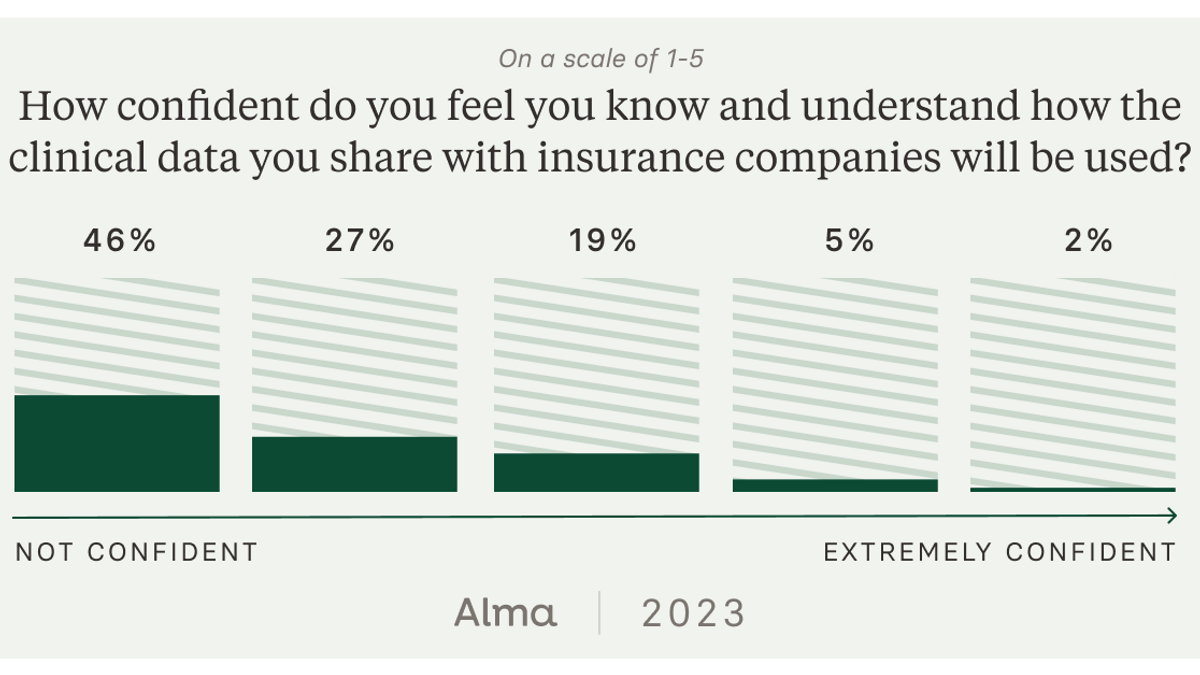

One barrier to broader adoption of assessments is that therapists are not sure how clinical data will be used by insurance companies. In fact, our survey showed 74% of clinicians aren't confident how insurance companies use this data.

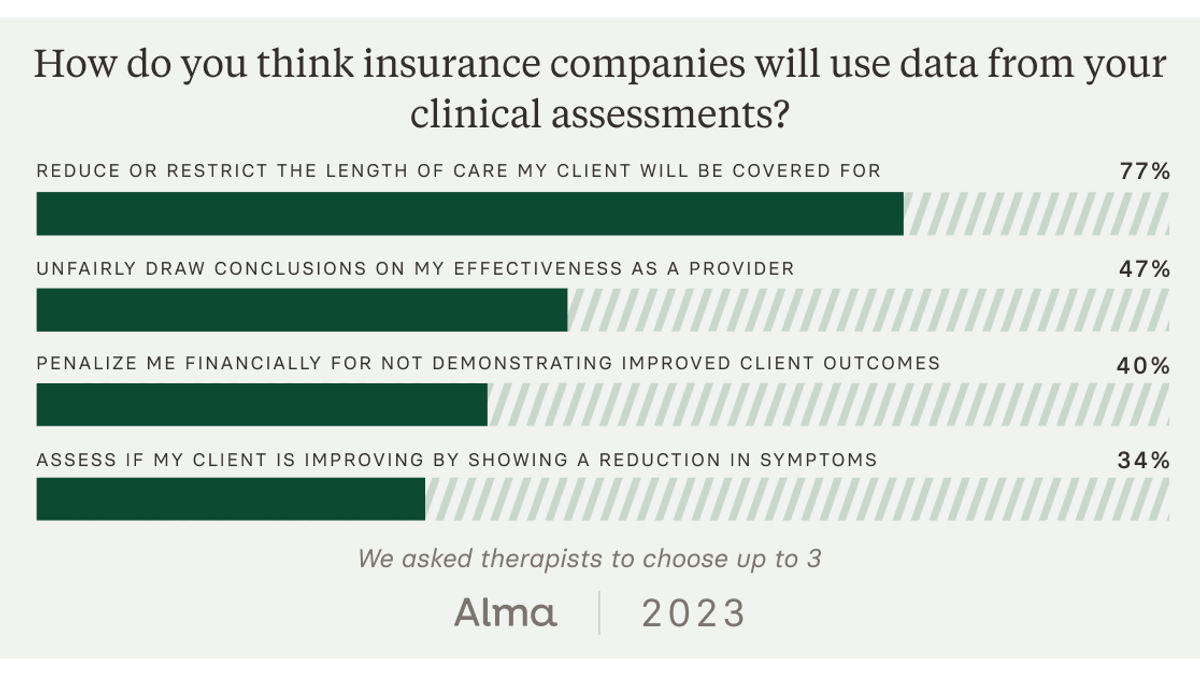

These findings offer one explanation as to why therapists are reluctant to re-assess clients. Nearly two-thirds of therapists (63%) express concern that insurance companies would use data from clinical assessments to restrict or block treatment.

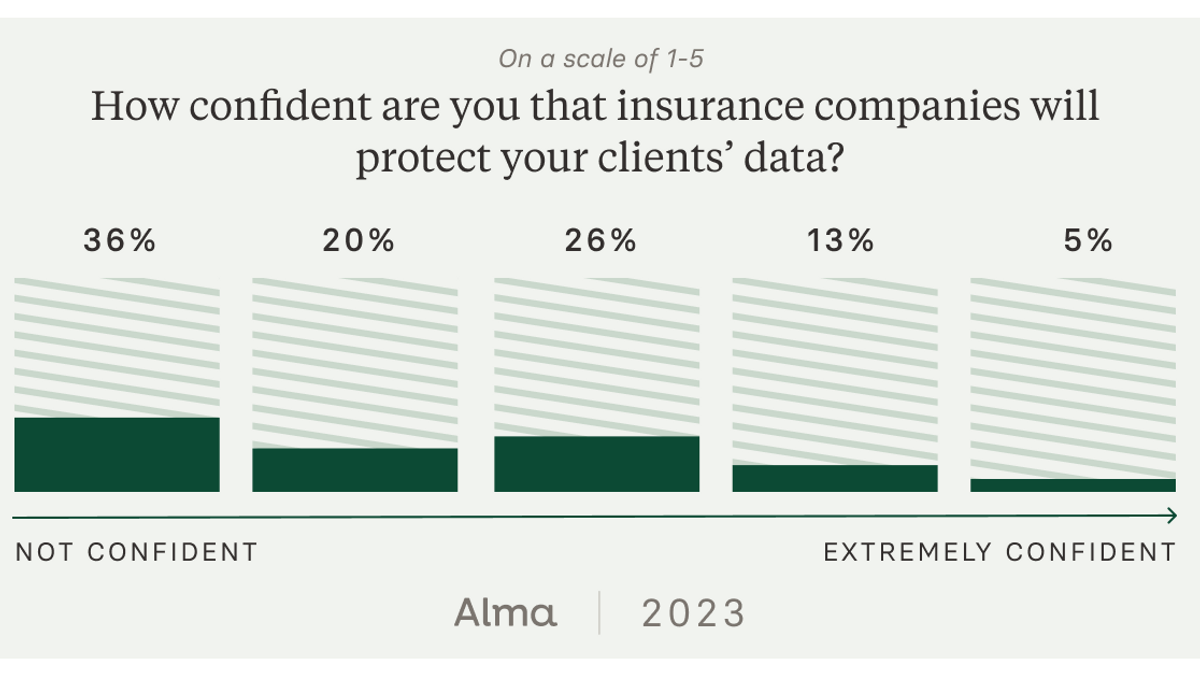

We also learned that most therapists have worries about the security of their clients’ information. 56% of the therapists Alma surveyed don’t believe insurance companies adequately protect patient information from data breaches. Clinicians have even less confidence in tech platforms, with only 37% feeling confident that their clinical data is secure on these products.

In reality; health insurance companies are continuing to explore the best approach to measuring behavioral health care. Assessments, at face value, offer a good deal of potential for all involved:

- Patients are empowered with information about their treatment goals and progress.

- Providers can get financial incentives and enhanced rates.

- Insurance networks can more efficiently cover the care their members need.

The real problem is that today’s assessments attempt to measure outcomes through only one quantitative measure, when — in reality — quantitative data is just one piece of the puzzle.

These findings expose huge opportunities for therapists, insurance networks, and human-centered therapy platforms to work even more closely on a shared approach to clinical assessment that includes qualitative and quantitative evidence.

What high-quality therapy (really) looks like

Quantitative clinical assessments are valuable — yet incomplete — views of progress in therapy. So, how can we know when therapy is working?

At Alma, we believe that expanding definitions of quality (and the indicators we use to demonstrate it) is essential. We need to consider therapists’ work with their clients in a holistic manner, and one that accounts for nuance between individual people’s mental health journeys.

We asked providers to share which factors are most important in assessing how therapy is going. The result? Three clear criteria for measuring the quality of care:

- improvement in client functioning (56%)

- reduction of client’s symptoms (42%)

- the strength of the client-therapists relationship (42%)

Improvement in functioning

A majority of therapists surveyed (56%) indicated that the most important signal of effective therapy is functional improvement in the client.

Most clinical assessments are problem centered; focusing singularly on symptom reduction. With this limited perspective comes the limitations of diagnosis itself, like reification and condition confusion.

By including — and even centering — client functioning, providers have an opportunity to measure what matters most to clients.

Reduction of symptoms

Measuring the reduction of symptoms is primarily how common clinical assessments measure success today. There is certainly opportunity for more holistic measures of success in therapy. And, 42% of therapists still find it important to track how therapy can reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety, and more.

This is great news for mental health care systems.

What this statistic tells us is that behavioral health providers deeply value the ability to measure symptom reduction, which is exactly what existing assessments like the PHQ-9 are designed to do. What’s missing are ways to supplement this information with more holistic, qualitative, and inclusive measures of success.

Therapeutic alliance

Evidence shows that the relationship between a therapist and their client is among the most critical elements of successful treatment.

Effective treatment of Complex PTSD, for example, may require months of relationship work, building rapport with a client who understandably struggles to extend trust. In this case, it wouldn’t be reasonable to expect healing — and certainly not symptom reduction — without the foundation of a therapeutic alliance.

It can be hard for clients to feel the immense progress they are making when the only markers are symptom-centered goals. In reality, connecting with a therapist that fits your needs is a critical foundation for the work of therapy.

Elevating therapists’ voices to create a universal definition of “quality”

Therapist voices are underrepresented in the conversation around measuring the quality of therapy. This oversight has harbored a skepticism that has dissuaded clinicians from adopting clinical assessments like the PHQ-9.

Assessments, however, can be used to equip providers with meaningful and clinically useful insights that contribute to a more comprehensive view of progress.

Clients, clinicians, and insurance companies all stand to benefit from the holistic assessment of therapy outcomes. But first, therapists will need to be granted a seat at the table.

In order to achieve a shared definition for quality mental health care, the perspective of providers will need to be centered.

Sep 19, 2023

Looking for a therapist?

Get tips on finding a therapist who gets you.

By submitting this form, you are agreeing to Alma's privacy policy.